970x125

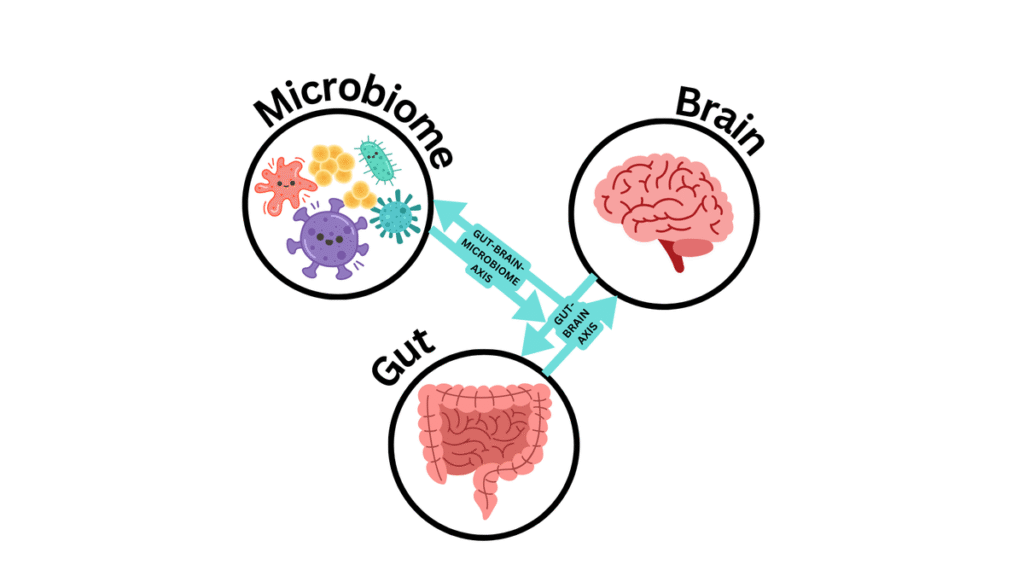

As mental health awareness gains momentum in India, a surreptitious menace is insidiously undermining this edifice of progress: the unbridled use of antibiotics. Whilst the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is ubiquitously acknowledged as a formidable public health hazard, its profound implications on mental well-being remain underexamined. At the epicentre of this conundrum lies the intricate gut-brain axis—a labyrinthine communication nexus between the gastrointestinal apparatus and the cerebral cortex.

970x125

Nascent research suggests that perturbations in gut microbiota, frequently precipitated by overzealous antibiotic consumption, may significantly contribute to the aetiology of anxiety, depression, and cognitive degeneration. In a country where antibiotics are often taken sans prescription or medical oversight, this gut-brain axis nexus demands an urgent and paradigmatic shift in attention for remedial measures to mitigate this silent yet calamitous crisis.

Antibiotic consumption

India occupies a distressing prominence in the global hierarchy of antibiotic consumption. The trifecta of over-the-counter accessibility, rampant self-medication, and limited public awareness has cultivated an entrenched culture of antibiotic overutilisation. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was accountable for an estimated 2,67,000 fatalities in India in 2021, with projections forecasting an escalation to 1.2 million by 2030, should prevailing trends continue.

A seminal study published in 2022 in The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia revealed a disquieting statistic: nearly half of all antibiotics consumed in India comprised unapproved formulations, exacerbating the threat of resistance. This egregious misuse not only fuels the conflagration of AMR but also precipitates a deleterious impact on the gut’s microbial diversity—a vital constituent of mental wellbeing.

What’s in the gut

The gastrointestinal tract harbours trillions of microorganisms that exert a profound influence on the biosynthesis of pivotal neurotransmitters, including serotonin and dopamine. These chemical messengers orchestrate the regulation of mood, sleep-wake cycles, and stress responses, and so, the gut plays an integral role in maintaining neurological homeostasis. When antibiotics disrupt this delicate microbial equilibrium, the repercussions can resonate throughout the nervous system, potentially precipitating a cascade of downstream effects.

Pioneering research from institutions such as the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) has initiated an exploration of the intricate relationship between gut dysbiosis and psychiatric maladies. Although the scientific discourse is still evolving, the accumulating evidence is sufficiently compelling to justify the implementation of targeted public health interventions towards a proactive and informed response to mitigate the burgeoning threat of gut-related psychiatric disorders.

The ramifications of microbial perturbation extend beyond mere biochemical imbalances; they encompass a broader psychosocial dimension that implicates the very fabric of human experience. The gut microbiota, often romanticised as the “second brain,” is not merely a passive consortium of bacteria, but an active participant in neurochemical symphony. Through the production of short-chain fatty acids, modulation of the immune system, and interaction with the vagus nerve, these microorganisms wield influence over neurodevelopmental trajectories and behavioural phenotypes.

Indeed, the burgeoning field of psychobiotics—a portmanteau term coined to describe probiotics and prebiotics that confer mental health benefits—has illuminated the therapeutic potential of modulating gut flora to ameliorate psychiatric symptoms. A 2020 meta-analysis published in Frontiers in Psychiatry revealed that probiotic supplementation was associated with significant reductions in depressive symptoms, particularly among individuals with mild to moderate depression. Such findings underscore the plausibility of gut-targeted interventions as adjuncts to conventional psychiatric care, especially in a nation like India where mental health infrastructure remains woefully inadequate.

Lack of awareness

Compounding this crisis is the paucity of public awareness regarding the gut-brain axis and its susceptibility to pharmacological insult. The average Indian consumer, often bereft of access to nuanced medical counsel, remains oblivious to the long-term consequences of indiscriminate antibiotic use. The cultural proclivity towards “quick fixes” and the valorisation of pharmaceutical interventions over lifestyle modifications further entrench this paradigm. In rural and semi-urban locales, where healthcare access is fragmented and regulatory oversight lax, antibiotics are dispensed easily, and without prescription—frequently for viral infections where they are not only ineffective but actively deleterious.

Moreover, the economic incentives that drive antibiotic over-prescription cannot be ignored. Private practitioners, operating within a fee-for-service model, may be inclined to prescribe antibiotics to appease patient expectations or expedite symptomatic relief. Pharmacies, often unregulated, serve as de facto dispensaries, offering potent medications without requisite prescriptions. This confluence of systemic vulnerabilities and behavioural predispositions has rendered India a fertile ground for AMR proliferation and microbial dysbiosis.

The implications for mental health are manifold. Dysbiosis-induced inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder, with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-alpha observed in affected individuals. These inflammatory mediators can traverse the blood-brain barrier, altering neurotransmitter metabolism and neuroplasticity. Furthermore, gut-derived metabolites like butyrate and propionate have been shown to influence gene expression in the brain, modulating synaptic function and stress reactivity.

Does what happens in your stomach affect your brain and how? | In Focus podcast

Need for interventions

In this context, the intersection of microbiology and psychiatry assumes profound significance. It invites a reconceptualisation of mental illness—not merely as a cerebral aberration but as a systemic dysfunction with gastrointestinal antecedents. Such a paradigm shift necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating gastroenterology, psychiatry, nutrition, and public health to forge holistic interventions.

Encouragingly, India possesses a rich repository of traditional knowledge that can be harnessed to promote gut health. Fermented foods—ubiquitous in Indian cuisine—such as curd, idli, dosa, and pickles, serve as natural probiotics, fostering microbial diversity and resilience. My grandfather swears by a spoonful of homemade curd after every meal—a ritual I once dismissed as quaint and old-fashioned. Yet, as scientific understanding of probiotics deepens, it’s clear that tradition was ahead of its time. Today, research affirms what our elders intuitively knew: the gut is not merely a digestive organ, but a vital cornerstone of mental equilibrium.

Public health campaigns must therefore pivot towards education and empowerment. The National Health Mission and Ayushman Bharat can incorporate gut-brain literacy into their outreach programmes, elucidating the dangers of antibiotic misuse and the virtues of dietary modulation. School curricula can embed modules on microbiome science, cultivating a generation of informed citizens. Media platforms, both traditional and digital, can amplify narratives that valorise microbial stewardship and mental wellbeing.

Simultaneously, regulatory reform is imperative. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) must enforce stringent controls on antibiotic dispensation, mandating prescription-only access and penalising non-compliance. More surveillance systems such as INSAR (Indian Network for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance), which is now part of a broader network, should be created and integrated with mental health metrics to elucidate correlations and inform policy. Investment in microbiome research, particularly within Indian populations, can yield context-specific insights and therapeutic innovations.

Clinicians, too, must recalibrate their praxis. Antibiotic stewardship should be embedded within medical training, sensitising practitioners to the collateral damage of pharmacological interventions. Psychiatric evaluations can incorporate gastrointestinal assessments, recognising the bidirectional interplay between gut and mind. Nutritional counselling, often relegated to ancillary status, must be foregrounded as a cornerstone of mental health care.

Transcending disciplines

Ultimately, the gut-brain axis offers a compelling lens through which to interrogate the mental health crisis in India. It reveals the hidden costs of antibiotic overuse—not merely in terms of microbial resistance but in the erosion of emotional resilience and cognitive vitality. It beckons an overhaul in medical thought, one that transcends disciplinary silos and embraces the complexity of human biology.

As India strides towards a more enlightened discourse on mental health, it must not overlook the microbial foundations of wellbeing. The gut, long relegated to the periphery of psychiatric inquiry, deserves its rightful place at the centre of public health strategy. By safeguarding microbial diversity, curbing antibiotic misuse, and embracing integrative care, India can fortify the minds of its citizens—one microbe at a time.

(Rashikkha Ra Iyer is a multidisciplinary clinician working in the U.K., specialising in the delivery of clinical interventions in forensic settings Rashikkha.RaIyer@outlook.com)

970x125