970x125

This story originally appeared in Kids Today, Vox’s newsletter about kids, for everyone. Sign up here for future editions.

970x125

I’m on vacation this week, so instead of a regular newsletter, I decided to examine a children’s classic that has been taking up a lot of my brain space lately. Back next week!

Raising children frequently offers one the opportunity to revisit the touchstones of one’s youth with a more experienced, critical eye. Who among us has not wondered how Garfield knows that it is Monday, or why Mickey is a mouse who owns a dog?

But perhaps no artifact of children’s pop culture feels more bizarre, more confounding, or, on closer inspection, more fascinating, to me than the multivolume story of Amelia Bedelia.

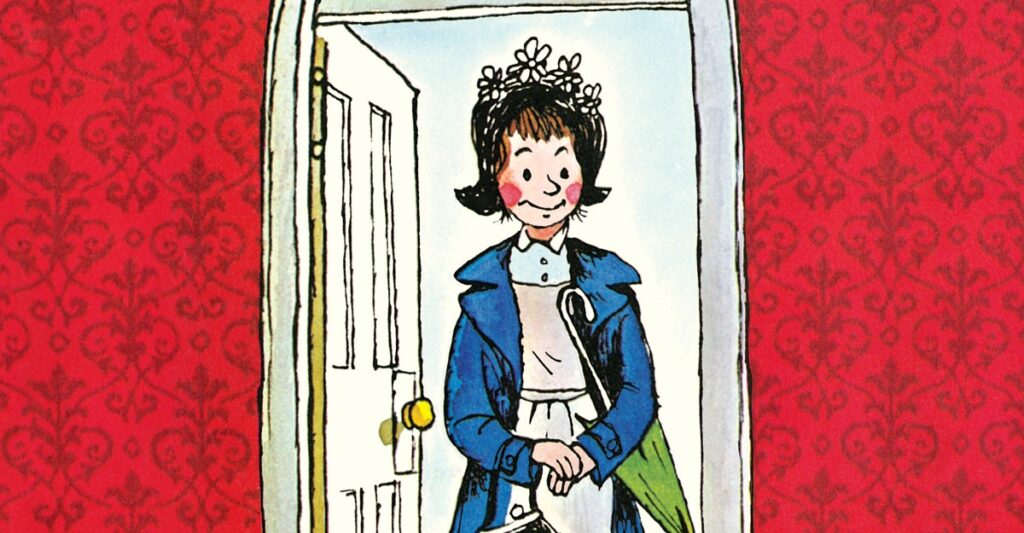

Written by Peggy Parish from 1963 to 1988, and continued by her nephew Herman for decades after, the Amelia Bedelia stories revolve around the eponymous Amelia, a rosy-cheeked woman with a starched apron and a perpetual smile who spends her days absolutely laying waste to her employers’ home.

Asked to “change the towels,” she cuts them to pieces. Asked to check Mr. Rogers’ shirts, she covers them with a checkerboard pattern. Asked to strip the sheets off a bed, she tears them to shreds.

Part of the pleasure of revisiting the Parish oeuvre is just how strange even the supposedly normal requests made by Mr. and Mrs. Rogers seem today, some 40 to 60 years after they were first issued. At one point, Mrs. Rogers asks Amelia Bedelia to “dress the chicken,” so she stuffs a raw chicken into some lederhosen. But what was she supposed to do with the chicken carcass she was given? Marinate it? What is this lost art of chicken dressing?

My core question, though, revolves around Ms. Bedelia herself: What exactly is it that makes her not merely misinterpret her employers’ instructions, but interpret them in the most floridly destructive way possible?

The standard explanation is that Amelia Bedelia takes her bosses’ commands too literally — failing to understand colloquialisms like “draw the drapes,” for example, she produces a sketch of them instead. One popular interpretation is that Amelia is autistic, and some autistic commentators have described finding traits in common with Amelia Bedelia or even learning common idioms from the books.

She’s someone who’s supposed to follow other people’s commands, and who instead performs bizarre acts that make those commands look silly.

Under this interpretation, Amelia wants to do what she’s asked; she just has trouble figuring out what that is (understandable given some of her bosses’ arcane assignments). There’s another school of thought, however, that asks whether the chaos Amelia produces might be a little bit intentional.

Given the way she frustrates and flummoxes her wealthy bosses, it’s not surprising that some see Amelia as a class warrior. For the New Yorker’s Sarah Blackwood, she’s Bartleby in an apron, “a figure of rebellion: against the work that women do in the home, against the work that lower-class women do for upper-class women.”

It’s instructive to see which tasks Mrs. Rogers delegates to Amelia. In particular, the maid is supposed to act as a kind of prep cook for the lady of the house, tasked with paring the vegetables (she puts them together in pairs, obvs), measuring cups of rice (she fills teacups with rice and then uses a tape measure), and, of course, dressing the chicken (again: what?).

Mrs. Rogers, emerging from her limousine wearing a fur stole, intends to finish the process of making dinner, and presumably get credit from her husband for her wonderful cooking. But her plans are upended when Amelia not only royally screws up all the prep tasks, but also makes pies and other baked goods so delicious that no one is thinking about dinner anyway (and also no one can bear to fire her).

Amelia Bedelia gets the upper hand, turning repetitive, invisible, literally thankless labor into highly visible performance art, destroying her bosses’ property and getting paid to do it.

I do not think Peggy Parish intentionally wrote Amelia Bedelia as a working-class revolutionary, but I do think there’s a bit of the trickster in her, despite her innocent demeanor (when she “changes” the towels, for example, she cuts a jack-o-lantern grin into one of them). I think my children, who are even further removed than I am from a world in which people drew drapes, like her because she is an adult who does silly things, a category of character that children tend to enjoy (see also Peppa Pig’s father, Daddy Pig, who reads maps upside down and once accidentally fell out of an airplane).

It’s not just my kids who weirdly reach for a book about a mid-century maid doing chores they can’t begin to understand. By the eve of her 50th anniversary in 2012, stories of Amelia Bedelia had sold over 35 million copies in the US alone. The character remains popular enough today that Herman Parish wrote an updated version in the 2010s and 2020s in which Amelia is no longer a servant, but a child whose misunderstandings take place on field trips and family house-hunting expeditions.

My kids don’t like this version as much, and I can see why. The core of Amelia Bedelia isn’t just that she has trouble with figures of speech. It’s that she’s someone who’s supposed to follow other people’s commands, and who instead performs bizarre acts that make those commands look silly.

For a child — someone constantly being told what to do in terms that are often less than clear, by people who seem to hold all the power — what could be more satisfying?

970x125