970x125

Somewhere far from the Grand Line, a pirate flag from Eiichiro Oda’s Japanese manga and anime series, One Piece, has been making a divisive kind of landfall. Across Indonesia, ahead of the country’s Independence Day on August 17, the Strawhat Pirates’ Jolly Roger — the flag of Monkey D. Luffy and his fictional crew — had been hoisted beside doorways, pinned to the backs of vehicles, and flown in place of the national red and white.

970x125

The image of the iconic grinning skull in a straw hat has spread far enough to catch the attention of the state. For many it was a wordless declaration that the state had been failing its people. A deputy house speaker condemned the flag as an “attempt to divide the nation.” Another lawmaker hinted at treason. One senior aide to President Prabowo Subianto warned that the symbol, flown beside Indonesia’s red-and-white, could undermine the national flag itself.

A graffiti of the pirate flag from Japanese anime One Piece, adopted by some Indonesians as a symbol of frustration with their government, is seen on a street in Sukoharjo, Central Java, on August 6, 2025, ahead of the country’s 80th Independence Day

| Photo Credit:

AFP

If you know One Piece, you probably see it already. In the iconic world Oda has built since 1997 — of colourful pirates of all shapes and sizes fighting back against corrupt marines, genocidal monarchs, and a “World Government” that erases history — the Jolly Roger is precisely the emblem you would fly if you loved your country but could no longer stomach what its rulers had made of it. The pirate story about friendship and treasure has long been a parable about dismantling tyranny. And if Luffy and his Strawhats existed in our world, the same officials who drape themselves in jingoist patriotism would likely call them what they routinely brand so many dissidents of oppression in the struggle for liberation.

Conjuring the ‘enemy’

History is replete with moments when the label “terrorist” has been stretched to fit whatever shape power needed it to. British colonial administrators used it to discredit Indian revolutionaries; apartheid South Africa applied it to Nelson Mandela. The word’s elasticity has long allowed those in authority to blur the line between “public enemy” and “liberator”. One Piece’s World Government perfects this technique, though the story also acknowledges that violence and extremism are real forces in the world, not simply fictions conjured by propaganda.

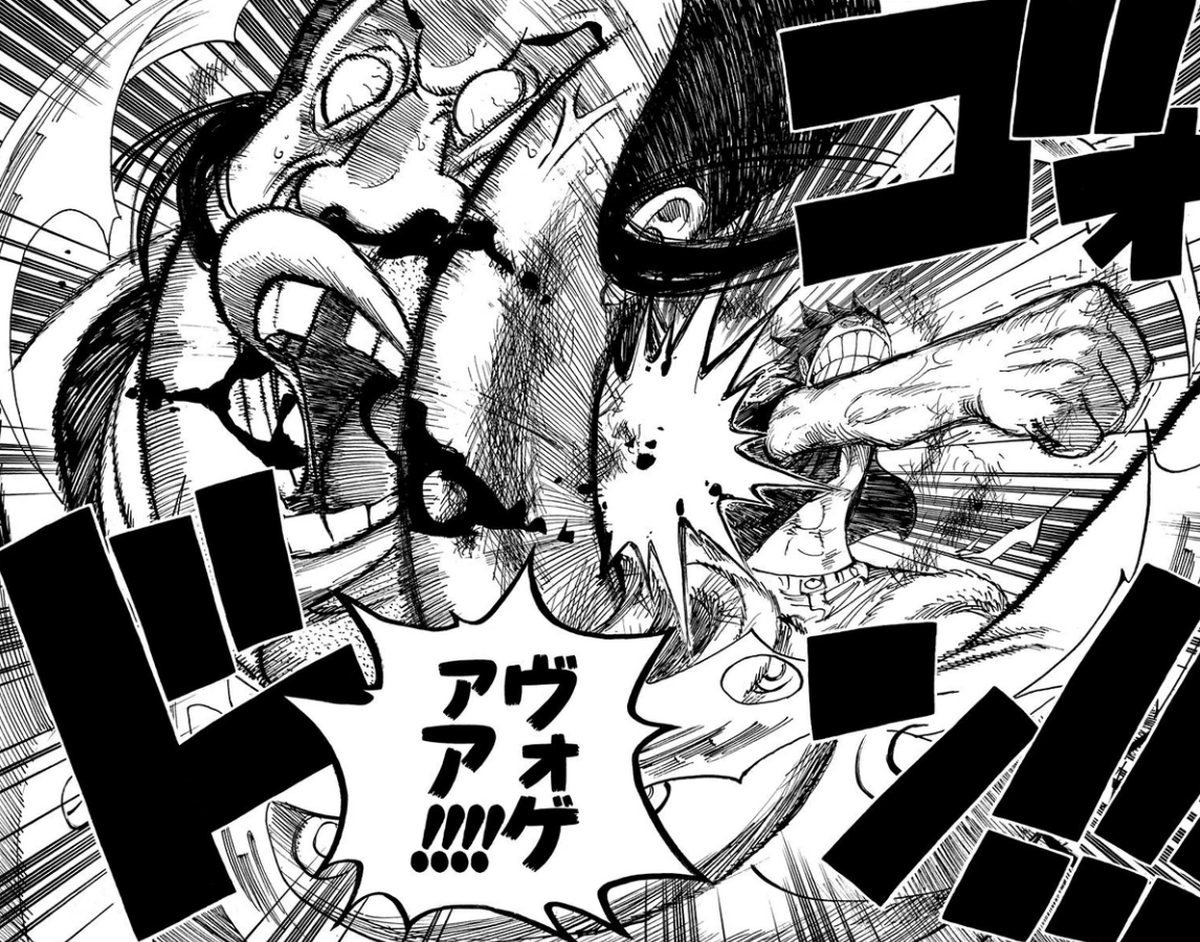

A panel from the ‘One Piece’ manga depicts Monkey D. Luffy ordering his crewmate Usopp to shoot down the flag of the World Government

| Photo Credit:

VIZ Media

In the series, the state’s propaganda machine works tirelessly to recast dissent as danger. Archaeologists on Ohara, guilty of preserving forbidden history; the people of Alabasta, resisting a manufactured insurgency; the Shandians of Skypiea, holding on to land in the face of forced displacement — all are folded into the same caricature as “enemies of peace”. In the broadcasts of the marines’ war correspondents, like Big News Morgans, state violence is sanctified and its victims are rendered villains.

And yet, the Strawhats are not innocent of the charge that they are a threat to the established order. They have torched government flags, attacked fortified bases, and aided revolutions in occupied territories. Before the eyes of the whole world, they have declared open war on the World Government. By the definitions in a government dossier, these are acts of terrorism. What One Piece insists on however, is that such acts cannot be divorced from the conditions that provoke them, and that sometimes the refusal to accept a peace built on the backs of the oppressed is a moral imperative.

After all, buried deep in the rarely-leafed pages of the Geneva Conventions (namely Additional Protocol I to Article 1(4)) grant armed resistance to colonial domination or alien occupation the dignity of national liberation and self-determination. Which means, unlikely as it sounds, that even a silly, rubber boy with a dream operates in compliance with international humanitarian law.

A politics of liberation

The genius of One Piece is that it wears its politics on its sleeve while masquerading as a funny pirate story. Luffy is no Robin Hood, content to topple one bad king and prop up another. Dense and blockheaded he may be, the Strawhat captain seeks nothing less than the liberation of the global oppressed and the destruction of the order that props up oppressors in the first place.

Time and again, the series drags the Strawhats into conflicts where the moral stakes are absolute. On Fish-Man Island, systemic racism has festered for centuries, pitting species against each other. In Dressrosa, a king recognised by the World Government is in fact a warlord who tortures and enslaves his people. In Ohara, the state commits a full-scale genocide to prevent the truth from escaping.

You can draw parallels without even trying. The teaching guide Oda’s work has inspired among activists and educators likens the actions of the World Government to atrocities being commited in real time, in the real world. It is also no accident that the worst crimes in One Piece are the ones committed under the veneer of legality. The marines’ white coats are tailored for plausible deniability. And so to read the series as apolitical is to ignore its very essence, that law and order are meaningless when they serve only the powerful.

Gaza and the Strawhats

In its peculiarities of distilling moral clarity into more bite-sized food for thought, the Internet has been asking: would Luffy free Palestine? For One Piece fans, the answer is almost too obvious to bother with. Set the Strawhats down in Gaza and they’d treat the siege as just another unjust island to liberate — slipping food through blockades, toppling watchtowers, and unmaking walls. And they’d probably do it knowing full well that, in the eyes of the powers they’d crossed, they would definitely be branded criminals, extremists, or worse.

A panel from the ‘One Piece’ manga depicts Monkey D. Luffy punching a Celestial Dragon, a member of a group of individuals who are supposed descendants of the 20 kings who founded the World Government 800 years ago

| Photo Credit:

VIZ Media

Since late 2023, Israeli military operations in Gaza have killed thousands of civilians, destroyed hospitals and water systems, and forcibly displaced and starved more than a million people. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have reported patterns of conduct consistent with crimes against humanity and, in the judgment of the International Court of Justice, with acts that have consistently met the legal definition of genocide.

Under the logic of the World Government, Palestinians who resist this — whether by protest, or by breaking the siege, or by armed struggle — should be labeled terrorists. It is the same logic that sees no contradiction in flattening entire districts for “security” while denouncing stone-throwing as barbarism. It is the same logic that would put Luffy’s wanted poster on every wall from Tel Aviv to Washington.

One can argue the tactics, the morality, and the timing of any particular act of resistance. But the broad truth remains that the oppressors have always reserved for themselves the right to decide who is “legitimate” and who is an “enemy of peace.” In One Piece, as in Gaza, that propogated legitimacy has less to do with justice than with obedience.

Why they fear the flag

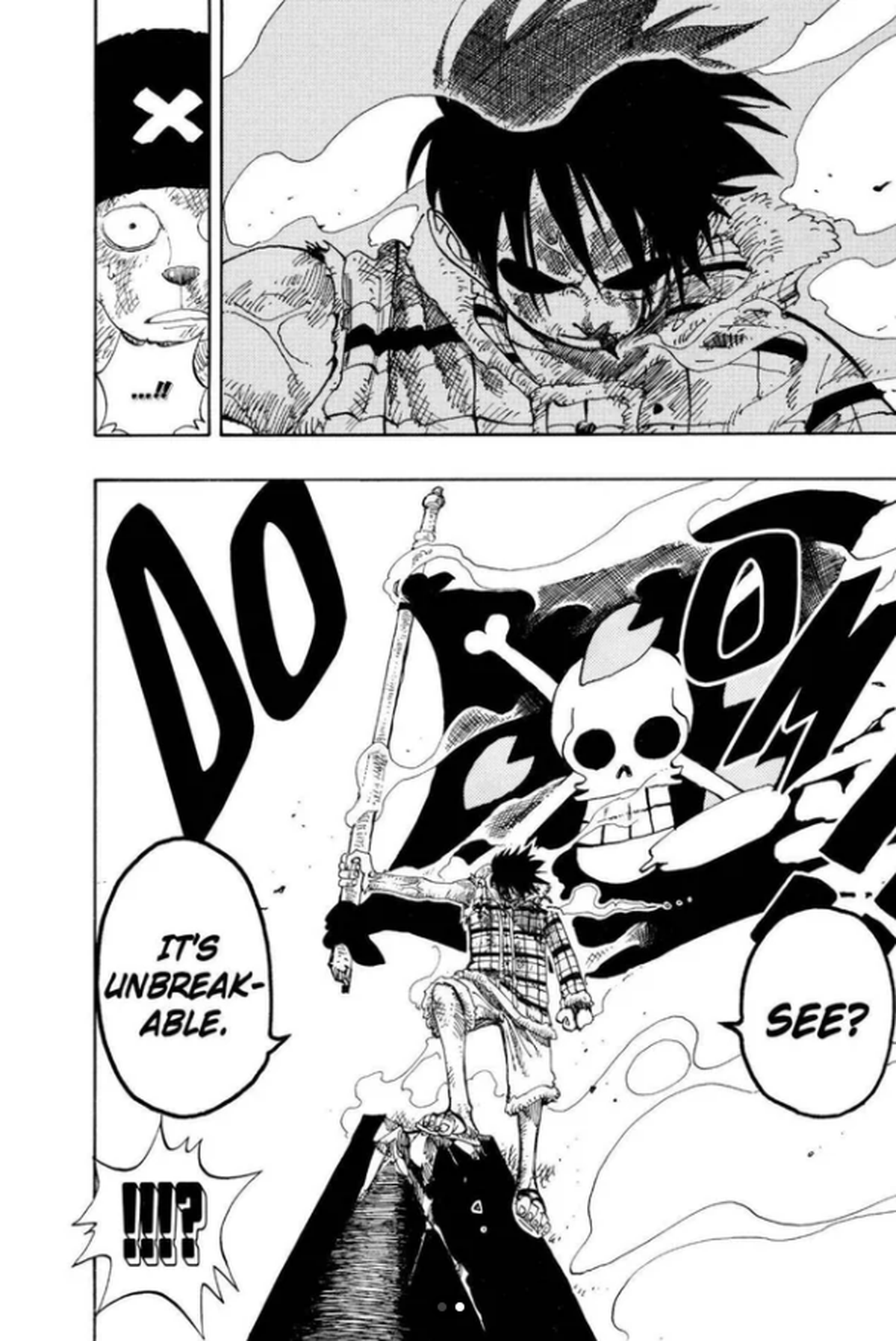

This is probably why, in Indonesia, the Strawhat flag’s sudden ubiquity has unsettled the political class. It’s clearly not just a bit of pop culture silliness or an act of otaku indulgence. It’s been a direct reminder that allegiances are not owed to governments simply because they wave the right flag. And it’s a symbol that has always said: our loyalty is to freedom and not to you.

When symbols like the Jolly Rogers or the keffiyeh emerge, they become threats precisely because they travel faster than the official rhetoric. They offer a shorthand for solidarity and a visual language that can’t be easily co-opted. Governments can try to confiscate them and make them illegal, but in doing so, they inadvertedly confirm what their critics have been saying all along: that their authority depends on controlling what people do, and more dangerously, what they can imagine.

“One Piece isn’t political”

There has nevertheless been a particularly frustrating strain of denial among some fans who insist that One Piece is just an adventure, and that politics is something imported into it by overzealous critics. The vapidity behind this thought is to liken Animal Farm to a children’s book about talking animals. It is to ignore that the series has, for more than two decades, depicted imperialism, systemic racism, propaganda, ethnic cleansing, and slavery as the very engines of its plot.

The politics of One Piece have never been incidental, in fact, one could argue they are its very marrow. Oda’s villains have always been strong in ways that mirror the worst habits of our own world. And his heroes have always been kind in ways that threaten the hierarchies we take for granted.

A panel from the ‘One Piece’ manga depicts Monkey D. Luffy standing resolute, not letting a Jolly Roger fall

| Photo Credit:

VIZ Media

It’s not unlike the moral spine that runs through James Gunn’s Superman, where the recent conversations around what the cape and the crest stand for have been far simpler, and far more subversive, than the partisan readings imposed on them. Strip away the stand-ins and you’re left with a hero who refuses to weigh human lives on the scales of alliance or convenience, who will stop a massacre whether it comes from a sanctioned ally or a sworn enemy. In that sense, Luffy and Superman share a dangerous trait in the eyes of the powerful with their loyalty to the stubborn idea that the vulnerable should be protected, even if it means being called the villain by those doing the harm.

If Luffy’s world ever bled into ours, you could imagine his ship turning up anywhere the strong have taken over or made a prison of someone else’s home. In Palestine, Sudan, the Congo, Ukraine, Xinjiang, Rakhine, Tibet, Tigray, Ireland, Syria, Artsakh, and Kurdistan — the names would change with the wind, but he would keep sailing until no one’s freedom depended on the permission of their oppressor.

970x125