970x125

For patients living with rare diseases in India, access to treatment often feels like a brief window of light in an otherwise dark tunnel. Lifesaving drugs exist, and for a while, they offer stability, dignity, and hope. But when public funding runs out, treatment abruptly stops, and hope disappears just as quickly.

970x125

This is the everyday reality for rare disease patients like P.A. Abhinand, 37, an Assistant Professor of Bioinformatics at Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research in Chennai. He lives with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) — a rare, progressive neuromuscular condition that causes the deterioration of motor neurons in the spinal cord.

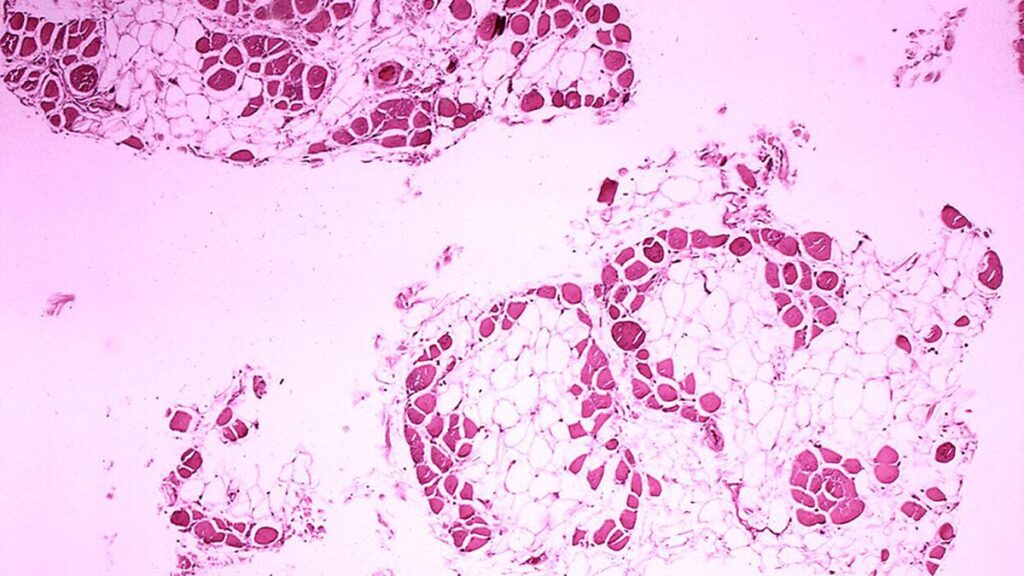

These neurons are responsible for transmitting signals from the brain to the muscles. Without them, muscles weaken over time, leading to severe physical disability. Many SMA patients become wheelchair-bound and gradually lose the ability to breathe and swallow independently.

Families struggle without continued support

In 2020, India’s drug regulator approved Risdiplam, the first and only treatment for SMA available in the country. Though not a cure, the oral medication helps stabilise the condition and slows down the muscle degeneration process.

For four years, Abhinand accessed Risdiplam through crowdfunding efforts and family support. The drug helped him avoid life-threatening infections and allowed him to actively pursue his teaching and research work. “It was the most productive phase of my career,” he says. “That medication gave me a chance to breathe better, live better.”

But that chance has now been taken away.

“One bottle costs around ₹6.66 lakh, and I need 30 bottles a year,” Abhinand explains. Although he qualifies under the National Policy for Rare Diseases (NPRD) launched by the Ministry of Health in 2021, with no renewal mechanism or continued support, he questions the point of the one-time fund.

Abhinand, who has spent years fighting for access and awareness, points out the deeper problem. “I still have some level of assistance and social capital. What about those who have nothing at all?” he asks.

Gaps in the national policy

The NPRD was introduced to offer financial support to patients with rare diseases at designated Centres of Excellence (CoEs). It classifies conditions into three categories: those treatable with one-time curative therapies; those requiring low-cost, long-term care; and those like SMA, Pompe disease, and Gaucher’s disease, which demand lifelong, expensive therapies.

Gaucher’s disease, for instance, is a rare genetic condition caused by a deficiency of the enzyme glucocerebrosidase, which helps break down fatty substances in the body. Without it, these substances accumulate in organs like the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, leading to symptoms such as organ enlargement, bone pain, low platelet counts, and chronic fatigue.

Abdul Rahman, a two-and-a-half-year-old from Uttar Pradesh, was diagnosed with Gaucher’s Disease in 2021 after months of medical visits across Kanpur, Lucknow, and Delhi. His family spent over ₹50 lakh on enzyme replacement injections, which temporarily stabilised his condition. But when the funds dried up in 2022, the therapy stopped. He now experiences severe pain, neurological complications, and behavioural issues.

Rahman’s father, Abdul Kalam, said that despite seeking help from AIIMS, Delhi —one of the country’s CoEs — they have not received additional support.

In Chennai, four-year-old S. Harish was also diagnosed with Gaucher’s. His father, Sathyaraj, recalls the first signs when the child’s stomach became abnormally hard and swollen. After diagnosis, Harish began receiving imiglucerase, the primary enzyme used in Gaucher’s treatment, through the Institute of Child Health in Egmore, one of the CoE.

Administered twice a month, the drug improved his condition. However, funding under NPRD was exhausted last week.

R. Karthik, a resident of Madurai, has a nine-year-old son with Pompe disease. It is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme acid alpha-glucosidase. This enzyme is essential for breaking down glycogen in cells. Without it, glycogen builds up in muscle tissues, causing progressive weakness in the heart, skeletal, and respiratory muscles.

Karthik’s family had to travel to Chennai twice a month for treatment. “It was hard to manage both the travel and my job in the northern part of the state. And now the drug has stopped,” he says.

Similarly, for Class 5 student Adrija Mudi and her parents, who live nearly 200 kilometres from Kolkata, travelling to AIIMS Delhi for treatment was an exhausting and costly ordeal. After exhausting government funding, the family managed to continue treatment briefly through donations and a discounted supply from the manufacturer. But now, even that support has ended. Adrija’s condition has since worsened — she is now experiencing both hearing and vision problems.

Call for urgent action

Advocacy groups say these stories are not isolated. Across India, more than 55 patients have exhausted the ₹50 lakh cap provided by NPRD. Many now face rapidly deteriorating health conditions with no hope of continued care.

In Tamil Nadu alone, at least six children are stranded without access to their life-saving medications. In Karnataka, over 24 patients face the same fate. Others from Delhi, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh are similarly affected.

“We don’t know what to do next,” D. Sathyaraj, father of Harish, says. “We can’t afford to buy it from the company directly.”

In October 2024, the Delhi High Court ruled in favour of continuing treatment for eligible patients under NPRD. However, the union government challenged the verdict in the Supreme Court through a Special Leave Petition.

The Supreme Court has since stayed the High Court’s decision, except for certain exceptions, and the matter is now being heard. Meanwhile, Patient organisations have been actively petitioning the judiciary to expedite hearings. Some have even written directly to the Chief Justice of India, seeking urgent intervention. Without institutional support or a clear funding mechanism, they warn, patients are slipping into critical stages — or worse, dying.

Raja Murugappan, a member of the Rare Diseases Support Society in Tamil Nadu and Puducherry, says they have written to the Prime Minister seeking urgent intervention. “Very few understand the seriousness of rare diseases,” he says. “Each time, it’s a struggle to access medication. People don’t realise that these treatments are lifelong. How can families be expected to afford such expensive drugs indefinitely?”

970x125